Real-time Responsiveness for Multimodal Digital Humans (Part 1) – The Full Stream-Calling Process

Multimodal digital humans typically refer to virtual entities equipped with various cognitive and interactive capabilities across modalities such as vision, hearing, and language. These digital humans possess human-like appearances, behaviors, and thought processes, enabling natural interaction with humans through diverse sensory and interactive modalities including vision, speech, actions, expressions, and gestures.

Given their human-like interaction methods, multimodal digital humans are widely applied in areas such as customer service, education, and entertainment.

The Challenge: Waterfall Calling

Many application scenarios for multimodal digital humans demand the highest possible degree of human likeness, which necessitates "near real-time" responsiveness.

What constitutes "near real-time"? A normal human typically responds within 1-3 seconds after hearing a question. However, currently known multimodal digital humans generally fail to meet this standard. The underlying reason is that the response generation process for multimodal digital humans is typically divided into four main steps, which are often executed sequentially – meaning the completion of one step is required before the next can begin:

- Speech Recognition: Converting spoken human voice into text.

- Large Model Response (LLM): Inputting text A into a large language model (LLM) to obtain text B as a response.

- Text to Speech (TTS): Converting the LLM-generated text B into human-like speech.

- Voice to Video: Generating the final digital human video response, synchronizing the digital human's appearance with the human-like speech.

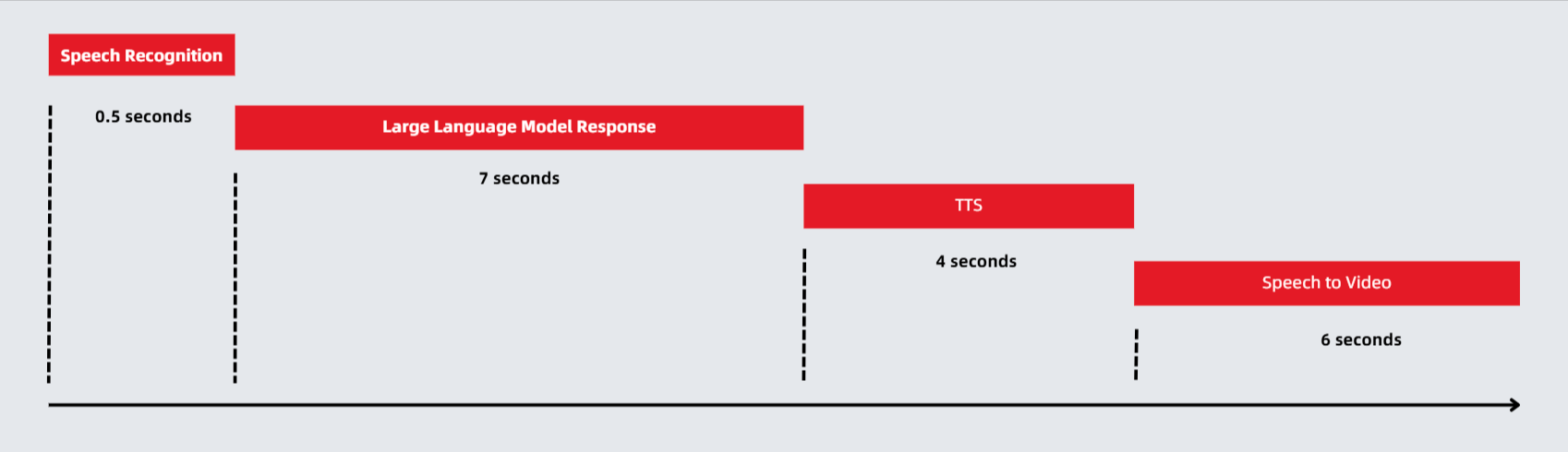

Let's consider an example:

Imagine a museum visitor asks an AI digital human the following questions:

"Who made this? What is the artist trying to say?"

The approximate execution time for each step would be:

- Speech Recognition: 0.5 seconds

- Large Model Response: 7 seconds

- TTS: 4 seconds

- Speech to Video: 6 seconds

If each step is executed sequentially, the total time spent would be 0.5 + 7 + 4 + 6 = 17.5 seconds. This far exceeds the user-acceptable response time of 1-3 seconds.

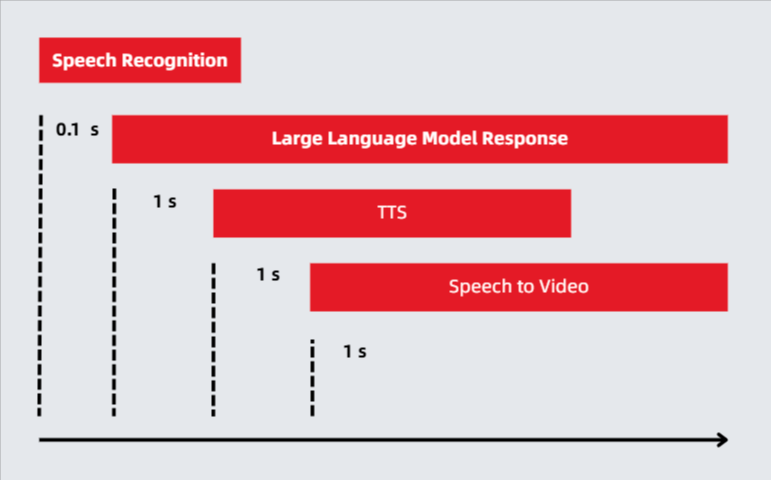

Therefore, XBIT Tech proposes using a "full stream-calling" approach. This means that each step doesn't have to wait for the complete execution of the previous one. Instead, at "breakpoints" where execution isn't fully finished, the next step can begin immediately. Let's look at the execution time with "full stream-calling" in an ideal scenario:

- Speech Recognition: 0.5 seconds

- Large Model Response: 1 seconds

- TTS: 1 second

- Speech to Video: 1 second

You can see that the processing time is significantly reduced to an acceptable range. To understand how to achieve this, let's break down each step.

1. Speech Recognition

Utilize "real-time speech recognition" APIs that begin to generate text upon receiving "partial speech data," rather than waiting for the entire audio segment. Moreover, these APIs continuously update and refine the recognized text as new speech data arrives. Google's best practice recommendation for "partial speech data" is every 0.1 seconds

Libraries like PyAudio can be used to directly read microphone audio data and then feed this data to the speech recognition API every 0.1 seconds.

2. Large Model Response (LLM)

This refers to the process of inputting speech-recognized text into a large language model to obtain its response.

This process can be chunked and streamed to the LLM to improve overall processing speed.

Specifically, when a pause in speech input is detected, signaling the end of the user's question, this segment of speech is immediately uploaded to the LLM for processing.

An exception arises when a user's question is particularly long. Waiting for them to finish speaking completely before uploading would significantly increase the number of tokens the LLM needs to process, thereby slowing down the response.

For such situations, XBIT Tech suggests a compromise: set a timeout t of 5 seconds. After t seconds, regardless of whether the user has finished speaking, the input is immediately uploaded to the LLM to seek a response. The expectation is that the LLM's semantic inference capabilities can "fill in the blanks" for parts the user hasn't yet spoken.

Furthermore, even if the LLM has already formulated a response, it should not interrupt the user's speech; it should wait until a user pause is detected before beginning to reply. This mirrors human interaction: some individuals possess quick minds and strong intuition, formulating answers even before you've finished speaking. However, out of politeness, they wait for you to conclude before responding. This method strikes a balance between "speed" and "accuracy."

For specialized fields, such as psychological counseling, where user questions often involve extensive context and are inherently long, making it impossible to gather all information within 5 seconds, the process can encourage users to ask multiple, shorter questions. Alternatively, t can be adjusted upwards as appropriate.

To determine pauses in user speech input, two common methods are used:

- Real-time speech recognition APIs often return a boolean flag with each recognition result, indicating whether the user has finished speaking. This judgment is based on a comprehensive analysis of the user's speech intonation, grammar, and vocabulary.

- Developers can set a "pause duration" t when calling the real-time speech recognition API to determine the end of user speech. If no speech input is received from the user (silence) for more than t seconds, it is considered a user input pause.

3. Text to Speech (TTS)

TTS refers to converting the text response from the large model into human-like speech for playback.

There are two ways to implement streaming TTS:

3.1. Word-by-Word Approach: Each word returned by the large model is immediately fed into the TTS API to obtain its corresponding audio file, which is then played sequentially. The advantage here is incredibly rapid and timely responses, with a return almost every 0.1 seconds. However, the disadvantage is significant: the resulting speech sounds like a robot, with words "bouncing" out one by one, lacking emotion and human-like naturalness.

3.2. Sentence-by-Sentence Approach: The content returned by the large model is fed to the TTS API sentence by sentence, according to sentence pauses, to convert it into human-like speech. Since most TTS APIs employ neural network methods, inputting an entire sentence results in speech with natural intonation and rhythm, sounding more lifelike. To prevent the conversion time from being too long, a prompt can be added when inputting to the large model: "Each sentence in the response should not exceed 30 words," ensuring that only short sentences are fed into the TTS API.

4. Voice to Video Generation

After obtaining an audio segment, it needs to be fed into a video generation API to produce a video with synchronized lip movements, body posture, and gestures.

The challenge in "streaming" this process lies in ensuring that each segmented video remains consistent in terms of body movements.

Here are two approaches:

4.1. Using "Video Generation Large Model" APIs: For each generation, define the starting frame as the frame immediately following the previous video segment. The advantage of this method is perfect synchronization of lip movements and body posture. However, the drawback is obvious: generation speed depends on the large model's computational speed. Therefore, this approach is suitable for digital humans with ample computational power and a high demand for accurate lip synchronization.

4.2. Pre-generating Continuously Moving Videos and Splicing: For example, a 10-second silent video is pre-generated and then cut into 10 one-second segments. Each one-second video segment is then synthesized with a one-second audio segment and spliced in the audio's sequential order. The lip movements in the spliced video may not be perfectly synchronized with every utterance, but they will visibly convey speaking. This method is suitable for animated digital humans that prioritize economic computational costs and have less stringent requirements for precise lip synchronization. The specific implementation method will be explained in detail in Xbit Tech's next technical article.

In conclusion, generating real-time responsive digital humans using the "full stream-calling" method is a comprehensive application of various technologies, primarily aiming for a balance between "user experience" and "technical cost." This article's proposed method is far from optimal and is intended merely as a starting point for discussion. We welcome feedback and suggestions from fellow professionals.